My little box of calmers

Music Performance Anxiety (MPA) afflicts the majority of musicians and the problem is not improving. For instance, over 50% of Australian orchestral musicians who responded to a 2014 study reported using substances like beta-blockers, alcohol, anxiolytics and anti-depressants to manage MPA. Ten years later, a new study in 2024 resulted in similar numbers. For my own sake, I want to explore the advice available from both violinists and non-violinists who are also MPA coaches, and see what works for me. On this page, I'll be sharing my discoveries, as described below.

Section 1: Tips, exercises and advice for technical and "practice" issues like:

intonation & tone production

tension & breathing

memory

shifting

string crossing

Section 2: Performance issues like:

anxiety & confidence

procrastination & motivation

identity, Imposter Syndrome & performance presentation

audience interaction and feedback

Advice, tips & exercises for Intonation

Susanna Klein: https://www.practizma.com/_files/ugd/120cba_ac9115bf25ff417582aeea12e3e6796d.pdf

Tip #1: "When teaching, I concentrate on four foundational concepts for playing in tune (....) mental visualisation, proprioception, listening and ease." These refer to fingerboard geography, a sense of our hands in space, auditory imagery and freedom from tension. (Klein, 2013, pp. 30-31). Exercises to practise these four concepts are:

(1) Mental visualisation = "One String Magic": Play a passage with the correct fingering but only on one string, so that although the notes sound wrong, the fingerboard geography in relation to intervals are correct.

(2) Proprioception = "All Fingers on Deck": Practise a troublesome shift in all the fingers in the same key, e.g. a tricky 4 - 4 major third is practised as a major third 1 - 1, 2 -2, 3 -3, 4-4 (original).

(3) Listening = "When in doubt, leave it out": Play a passage with just one note per bar, choosing the most harmonically significant note. Play it again with two notes per bar, etc.

(4) Freedom from tension = "Pedal Tones": Before every stopped note, play an open string. Strike then relax rather than keeping fingers pressed into the fingerboard / string.

Daniel Kurganov: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oac8Gjk03oI

[Paraphrasing:] Fix your intonation in a week by using Sevcik exercises to improve handframe and facility: Book 1: 24, 25, 26 and Book 2: 10. 19. 28. The crucial part of the player to use is aural rather than physical, because it is primarily about listening to find where the note is, rather than feeling a hand position. At first, do not drill. Do not play fast. Repetition is of no use until the note is played with accuracy every time, and then it is known securely in muscle memory. Then one can drill and play faster.

Kelly Jones

Two things that improved my intonation quickly:

Check the settings of the tuner app. My settings were wrong for several years, causing ongoing frustration for my violin teacher. My incorrect settings for TE Tuner were: Perfect 5ths instead of Pythagorean (Stretched Perfect 5ths) and guitar instead of strings, and not adjusting a further setting to orchestral / violin. Another mistake is, after tuning A = 441Hz or 442Hz, to tune the remaining three open strings to the tuner app instead of to each other. Check for a stillness of the beating when double-stopping the open strings.

Engaging in the #100DaysOfPractice challenge as an intonation bootcamp, focussing purely on playing the first four notes of G major in perfect tune relative to the violin's own resonance. Doing this extremely slowly, holding each note to hear the strongest, clearest, accurate intonation over and over until it becomes habitual, was an important exercise for me. Creating this aural and body muscle memory by sheer dint of repetition, twice a day, helped me break bad habits like sliding slightly, or altering my handframe a little to cope with a long third / short pinky situation.

Shifting

Grigory Kalinovsky: https://www.violinist.com/blog/laurie/20158/16960/

Shifting poses all kinds of issues, especially when there is tension in the shifts. "A lot of times, right before the shift, the shoulder locks," Kalinovsky said. This is very counter-productive, because shifting actually comes from the shoulder. He said that the larger muscles of the upper arm and shoulder bring the finger along, not the other way around.

Also, one should not let up on the bow during the shift to "hide" the shift. To avoid doing this, practice the bow stroke without the shift, then keep it the same when adding the shift. Or, instead of thinking of it as two notes, think of it as one note, with the shift as a "tail."

Tension and breathing

Noa Kageyama: https://bulletproofmusician.com/does-just-breathe-really-help-us-lower-anxiety-or-is-it-just-a-total-cliche/ (2024)

... slow, easy, deep breathing isn’t just a sign that you’re calm, but something you can consciously do to actively promote a more relaxed state.

Another tip I recently received from a former airline pilot (who in turn learned it from a Navy SEAL buddy of his) was that we sometimes focus too much on inhaling and taking in deep breaths. Instead, it can often be more helpful to focus on breathing out and getting rid of old air. As in, when you get to the end of a breath, gently push the rest of the air out, and let your lungs naturally fill themselves back up with fresh air.

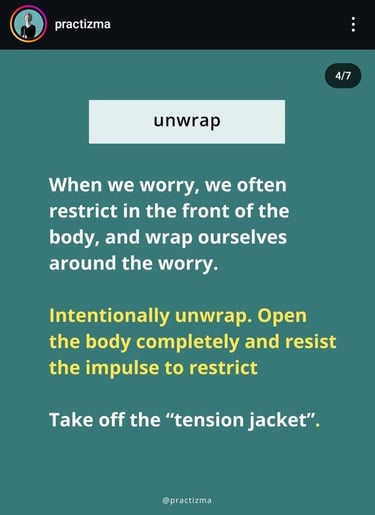

Susanna Klein: [The following are screenshots of posts on her Instagram account, Practizma]

Bowing patterns

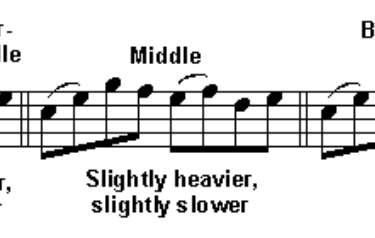

Simon Fischer, Basics

[Using Kreutzer, Etude No. 2]: Using bowing variations means to apply a specific bowing pattern to the whole study, e.g. bowing each group of four notes with two notes slurred, two notes separate, or three slurred, one separate, and so on. The simple repetition and the variety of note patterns that are covered, makes this one of the single most effective methods of practising and improving bow control.

....The most important thing is to listen carefully to the tone, catching every sound that comes out of the instrument. Each note must be clean, rounded and resonant, free of scratch or whistle.

One of the single most common bowing faults in tone production is bowing too far from the bridge with either too weak or too pressed a tone. Pay careful attention to the point of contact, playing near enough to the bridge for the string to provide sufficient support to the bow. One of the most powerful exercises for tone production consists of taking one group of notes and playing it at several different distances from the bridge. Repeat each bar several times, looking for exactly the right proportions of bow speed and weight.

Memory

Molly Gebrian

I would say if there's one magic bullet for practicing, it's get enough sleep. Sleep is amazing. I could talk all day about sleep.

....make the retrieval process automatic the way it needs to be. So practicing retrieval a lot, doing lots and lots of practice performances either in front of a video camera at home or friends, family, whatever, from memory to test that. Also practicing retrieving the information, not just from the beginning.

.... the videotape is like people watching you, right? And so it helps you cope with that feeling of, of being watched and to get over that sort of inherent need to sort of micromanage everything you're doing. And then the second thing they found that protects against [explicit monitoring that causes choking] is to for people to think about big picture things. So for us as musicians, that means phrasing, sound, whatever you're trying to convey emotionally to the audience, the more you focus on those things, the less you are able to explicitly monitor and it and it protects you.

Susanna Klein, 2023: https://www.thestrad.com/student-hub/the-anatomy-of-deliberate-practice-violinist-susanna-klein/15925.article

Use interleaved practice regularly. Interleaved practice avoids the brain going on cruise control and muscle memory taking over. During interleaved practice you will be learning more actively, but in less amount of time.

Two half-hour stints several hours apart is way better than one hour at a time. The more you space out your practice (think distributed, with big breaks), the more you have to dip into your long term memory to retrieve the information. This retrieval is vital to brain processing.

Anxiety and Confidence

John Beder, 2016: Link.

Composed (2016), a documentary directed by John Beder, is "a glimpse into stage fright [that] follows classical musicians as they navigate performance anxiety and discover effective strategies for coping with it. Link.

Susanna Klein, 2022: https://www.csmusic.net/content/articles/empowered-recording/

When I record to “practice my nerves,” I warm up but I don’t allow myself to practice the piece before the run-through. I treat the microphone like an audience. I get nervous for these takes quite naturally. My mantra is not to stop and treat it like a performance.

This type of recording is for developing nerves of steel, not listening acutely. It’s big picture work, not small picture analysis. Sometimes I listen the next day, sometimes I don’t. This is about understanding what happens under pressure. I have found that these recordings often sound better than I would have thought. That has been a wonderful surprise, but it only started happening after I started recording myself regularly in practice.

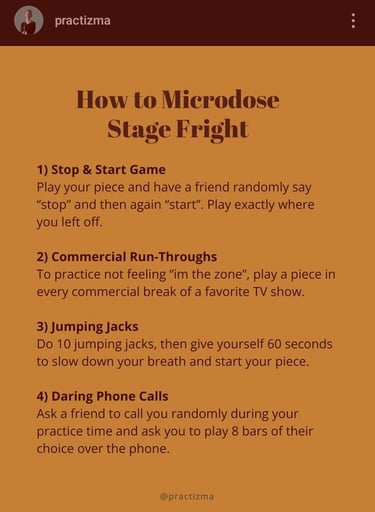

[The following screenshots are from Susanna Klein's Instagram account.]

Stephanie Faye Molicki, 2023. Neuroscience Paradigm Shift Mindset Mini Guidebook

Something to know about the hands: it is one of our first, most primal tools used in SELF-SOOTHING. Once we leave the womb, our hands become an extension of our desire to CHANGE OUR STATE. We often use the hand to grip or grasp something that we can ingest or consume. This is tied to the swallow reflex - which engages systems tied to the vagus nerve and helps induce a parasympathetic or rest and digest mode, a slowing down.

We also use our hands to grasp or seek for someone who will comfort us. This is tied to ‘seeking proximity’. This can also be translated into seeking social connectedness through communication (such as using our phone to contact someone).

Procrastination and Motivation

Susanna Klein, 2023: https://www.thestrad.com/student-hub/8-ways-to-make-practice-playful-susanna-klein/15924.article

... a playful approach makes any endeavour easier, more enjoyable, and more likely to be repeated in the future. In other words, ’play’ is the perfect approach for practice. According to research, play for adults is not trivial fluff. It stimulates the imagination and relaxes the body - good news for our technique. Play is kindling for our passion. Play encourages curiosity, it allows us to explore within practice rather than to endlessly repeat. Most importantly, it can imbue our most daring and difficult tasks with a sense of lightheartedness. Engaging in play allows us to dig deep without feeling overwhelmed. It invites us to be patient.

Pick a practice theme for the day to lighten your work and spur curiosity. For example, ’backwards day’ could be a day when you practise all your hard licks backwards, i.e. right to left. ’Dancing Day’ means you move around like crazy. Think of themes that address your to-do list, but in a fun way.

Susanna Klein, 2018:

Here are some examples of the types of New Year’s Resolutions that speak to discovery, efficiency, and transformation, i.e. goals that have to do with the process of learning, not the amount of time we devote to it.

Video record yourself at least once every single practice session

Play for a peer or friend for feedback once a week

Analyze a professional player’s bow movements by slowing down a YouTube video of their performance of my piece

Regularly sit in on a friend’s lesson and take notes for them – with your teacher, or another teacher, or even another instrument category

Perform for someone you have not performed for once a month

Make every practice session interesting, intriguing, and stimulating so it will maintain your curiosity. If you lose that sensation, it’s time for a break.

Session focus: Write on paper one process goal before each session (concentrating on sound, or bow distribution, or shifting speed, or patience, or intonation, or musical commitment, just as examples)

Change one fundamental technical flaw every three months by any means necessary

Ask questions of mentors and coaches in every single lesson/interaction

Concentrate on one aspect of playing at a time and break things into smaller and smaller components

Watch one YouTube tutorial per week in the hopes of discovering something new. If there is nothing new to you, self-praise yourself that you already know it!

When things are not working, do one thing at a time, don’t try to do everything at once.

Do something every week for your growth as a musician of which you are deeply afraid (for example play for an idol, contact a potential teacher, plant yourself in the first instead of second violin chair, post a practice video, play in public etc.)

Every other day, spend half of your practice time not playing – singing, score study, listening, counting.

Strategic self-encouragement: write down one thing you are particularly proud of at the end of each practice session.

Perform regularly in a place where your music will deeply touch the audience – a nursing home, a prison, a hospital bedside.

Susanna Klein, 2020: https://www.practizma.com/strings-article

Make it visible: e.g. make instrument visible between practice sessions; keep favourite piece open on music stand; keep goals on a sticky note on bathroom mirror; shut the computer off and charge your phone far away from you during practice (use a different device for practice apps);

Make it accountable: e.g. have a practice buddy; advertise to neighbours of weekly performance for ten minutes on the balcony / lawn; co-learn new repertoire with a friend sending milestone recordings each week then meet up to chat; make an a capella video with friends for social media;

Make it Fun, Pleasurable, Gamified: Make your practice room beautiful with your favourite comfort drink and a couple of biscuits; make it quirky and spontaneous with some interesting equipment to play with, e.g. baroque bow, quarter size bow, new rosin, left hand only, pizzicato only, etc.

Make your intentions Specific, write them down: Choose the time of day to practice and block it out in your calendar; choose three specific goals for a practice session; write on music in the margin dates for starting a new section; make sure practice time always includes fun, goofing off bits.

Goldilocks principle: scaffold difficulties, like choosing achievable but challenging repertoire, following a range of levels of musicians and not just the superstars; "Create the Muse" for yourself by choosing projects that are achievable rather than terrifying. HABITUAL and ACHIEVABLE.

Noa Kageyama, 2015: https://bulletproofmusician.com/temptation-bundling-how-to-stop-procrastinating-on-the-important-things-yet-still-indulge-in-guilty-pleasures-guilt-free/

Temptation bundling combines a guilty pleasure with a productive activity. It’s about removing the little speed bump that stands in the way of us getting started. And about helping us to build up stronger habits that are consistent with the long-term goals we are already committed to. Like doing some score study with cookies and milk. Reviewing tape of a recent performance while getting a foot massage (or with a glass of wine). Folding laundry or doing the dishes while watching Netflix.

The following screenshots are from Susanna Klein's Instagram account.

Identity, Imposter Syndrome, Performance Presentation

Noa Kageyama: https://bulletproofmusician.com/does-style-really-trump-substance/

It’s about looking engaged, present, free, and involved, rather than appearing disinterested, tentative, uncertain, or apologetic.

Audience Interaction and Feedback

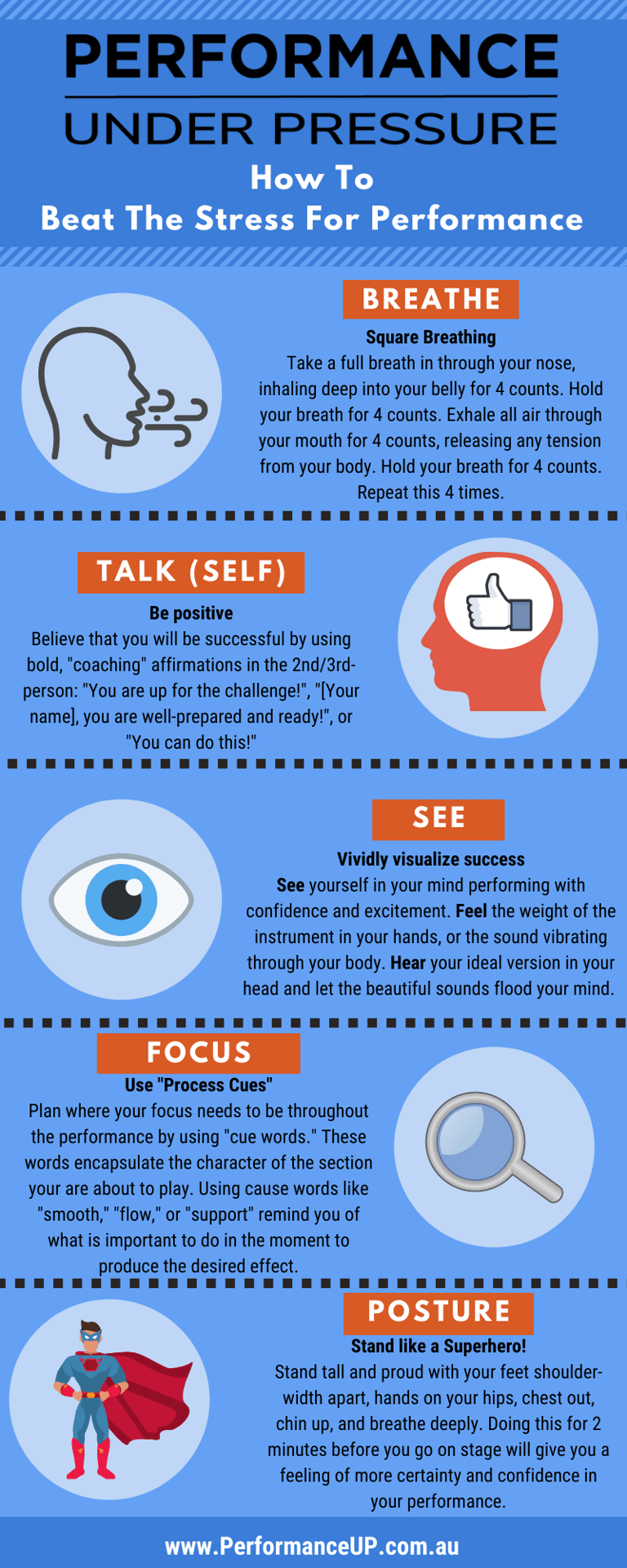

Mark Bain, Performance Under Pressure