Ching Chong

Published in "Fusion", a literary anthology competition for UNE students, the following autobiographical piece discusses what fusion means in terms of being biracial, in reality, for me.

CULTURAL IDENTITYRACISMCHINESEEAST / WEST

蔡亹平 Cai Menping

1/9/20257 min read

Left: Natives of Guangdong 广东, my great-aunt, great-great-grandmother, and great-grandmother (mother's father’s mother). Early 1900’s. Centre: My great-grandmother (mother’s mother’s mother) with three of her four children in Burwood, Sydney. 1930’s. Right: My mother, me as a baby, my older brother, father and older sister in Corowa, NSW. Note the blue shearer’s singlet and Tonka truck. 1970’s.

Ching Chong

Warning: Domestic violence, racism.

The fusion of A and B is... AB or C? When C exists, A and B have vanished, like the parents of the “Graveyard of the Fireflies” children, but C’s existence is a linear consequence of A and B. By contrast, AB is still living at home, either a filial child subservient to A and/or B, or maybe rebelling at home. Is a mixed-race child’s culture the fusion of AB or the fusion of C?

Until recently, I insisted that I was an AB fusion. I really believed there was no such thing as A vs. B. I'm a 3rd-gen Cantonese, 9th-gen mongrel descendant from a Staffordshire convict called Elizabeth Whitmore, and I believed that there was no such thing as East or West, either culturally or geographically. I’m an integrated whole, thus, where is that boundary? Is my sense of smell more Cantonese than Anglo? Is Russia East, Near East, Near-Middle East, Far East or Near West? How adventitious these divisions are. They’re merely cultural conventions, like Lao Tzu would say: black creates white, tall creates short, in creates out.

But I was brought up in rural white Australia (northern Tablelands NSW), speaking English, eating vegemite on toast, sausages and mash, bread and butter puddings, going to church on Sundays, and attending schools where the popular kids were blonde-haired and blue-eyed. My siblings and I were the only Chinese students at one rural NSW school, except for a boy that was literally called “Chinese Takeaway” by the other school kids. This was in the 1980’s.

In Sydney, I had two full-blood Cantonese cousins and their mother spoke fluent Cantonese. When I visited my very short, stout grandmother (d. 2009) in Strathfield, Sydney, she would swing with me down to the shops, rowing both walking canes like she was skiing along the pavement. In central Strathfield I would hear her happily chatter to shopkeepers in Cantonese, proudly showing off her grandchild. In the 1950’s, she had separated from her husband and raised her two children single-handedly, while also working as a secretary. The White Australia policy had a very strong impact on their lives. My mother, her only daughter, didn’t learn much Cantonese: she could count to ten, knew the names of lots of different foods and her mother would tell her to “xi shou” (洗手 wash your hands --- I’ve written the Mandarin as it sounds very similar). My mother mostly speak English at home, went to Central Baptist in the CBD, and they never visited Daoist temples anymore.

My father and mother did their first Acts of Fusion in their very early 20s (way too early), largely because my Nan Jones said, “Beverly would make a very good mother”. She did, too. My father was anti-Chinese. She was a timid, myopic wife, and when he smashed her glasses on her face, she rang Lifeline for help, who told her that she was a "doormat" and she should leave him. However, she stayed with her Aussie Battler, whose parenting and animal husbandry relied on fear and violence, not only whipping livestock until they were bloody and trembling, and shooting a "bad-tempered" animal, but also whipping the children and punching the wife. Talking back was dangerous. My mother assimilated very rapidly.

This method of fusing had many consequences. I was a very shy being. When I was in seventh grade in high school, I was given the role of “Ying Poo” the Chinaman, in the school play. I had a long black plait and spoke in a silly sing-song voice. I thought it was perfectly natural! During rehearsal one Saturday afternoon, I was too frightened to ask where the girl’s toilets were, and when going on stage for my part, my bladder burst and I ran off into the wings and the urine ran down my legs, flooding across the timber floorboards. It was terribly humiliating.

When I was about 16, after church one Sunday, I wished to say something about the sermon because I dared to disagree with the pastor. My father’s response was, “You can leave home immediately!” No talking back included no voicing of any dissenting opinion. Fundamentalist Protestantism taught me that God would strike me from heaven with some terrible punishment if I were disobedient and sinful. When I left the church at the age of 19, in second year uni, I was still arguing mentally with an imaginary God and genuinely feared that I’d cop an awful supernatural punishment. It took quite a while to stop feeling like a guilty evildoer.

Wiping out the B made me believe there was no such thing as East and West, let alone East vs. West. “Look at me! I'm Eastern and Western, so they aren’t mutually exclusive.” I said stuff like that then. I didn’t realise there was no B in my life.

Compartmentalising helped keep the fiction going. Sometimes, I realised that there was a massive, ancient culture out there, off-bounds, because I couldn’t understand even a single Chinese language. I knew some version of “你好吗?ni hao ma?” and “我很高兴认识你!wo hen gaoxing renshi ni!” because when I was 20, in 3rd year at Sydney Uni, I started an Adult Education course, but it was too hard to keep up. I visited Chinese suburbs, saw lots of unreadable Chinese advertising, hankered after foods in Chinese grocery shops that I couldn’t read the labels of. So much existed that I was ignorant of. But I still maintained, I was AB.

Enter COVID-19 in March 2020. My father decided it was a Chinese conspiracy to start and win WW3, parroting a list of reasons copied from Facebook. I think I saw red! I replied in an equally-bloody-minded way, listing dot points on why that was incredibly dumb idea. Is the Chinese government so stupid as to vandalise their economy and social cohesion? Or are they extreme masochists? Like the craven bully he really is, he ran away and would not dare speak to me. I certainly don’t invite dialogue as I see him as a perpetrator of domestic violence and racist abuse against my mother, siblings and myself. I think he should have done gaol time. He threw a hammer at my younger brother’s head, narrowly avoiding killing him. Although my three siblings (most of their children have blue eyes, some even have blonde hair) say there’s no point in challenging him, as “he’s never going to change / he’s too old / he’ll never apologise”, I continue on my path because I believe silence is compliance.

In late 2020, chewing over the disturbed feelings about my lost Chinese-ness, I flipped the bird and decided to start learning Mandarin Chinese. UTAS offered an online Diploma of Languages and I studied that part-time, switching to UNE’s Diploma of Modern Languages in 2022 for smaller tutorial classes --- thankfully, it was a very good decision! I’ve now been studying Chinese for four years, and know almost 6000 words.

Last year, I went to China for the first time – alone! Every language student wants to test their skills in a native environment. The food was mostly very confusing. I got ripped off a few times as I don’t have that essential native Chinese skill of bargaining.

That’s when it really hit me: the division between East and West really does exist. It’s not originally or innately political. That’s a consequence. As a side note, Australia has a strong political boundary drawn against China because of Australia’s political alliance with the US. The US and China are basically the two biggest political powers in the world. Because Australia’s culture is predominantly Western, it follows West-centric policies, while desperately trying to maintain peaceful relations with China, to maintain trade and economic stability.

While in China, I noticed things like:

Drivers changed lanes without waiting for a space to move into, yet there were no accidents

Roadworks that were terribly haphazard and lacked safety warnings or barriers, yet drivers seemed to have an amazing ability to adjust to their immediate surroundings

Chinese people I spent time with trusted the government, and showed pride and contentment rather than fear, anger and uneasiness as one would expect if living in a corrupt and authoritarian regime

Most people were slim, fit, active and down-to-earth

I rarely saw women wearing dresses or getting all fancied up, even in central Shanghai (except in the Bund)

The working hours were very long (e.g. post office is open on Sundays from 7am to 9pm)

Cities were very clean and cleaners were ubiquitous. There were no big machines and high tech; manual labour was predominant

Asking someone if they’ve eaten as a greeting makes sense when everyone is so slim and works so hard; it’s about helping each other be productive

Western fashions and behaviours are very trendy, yet most Chinese people I met could not speak English to save themselves, even at major city transport hub help desks!

I got the very strong sense that Chinese mainlanders are a united family. I felt safe, as though strangers were relatives. The fact that I got ripped off several times made me realise that, yes, I could belong to that family, but only if I learnt how the rules worked. With hundreds of years of Confucianism, that emphasises family, filial piety and social cohesion, and decades of single-child families creating strong bonds between unrelated children, the solidarity makes sense.

These are just my personal thoughts. China is not “home”, but nor is Australia “home”. I know how the rules work here in Australia as a “native” white, but I still feel bereft of part of my heritage. I’m 50% Southern Chinese by DNA but Cantonese culture and language are both very unfamiliar. Plus I hate the humidity! But I loved how no one in China who met me asked me what country I was from. Many people said they thought I was Chinese.

Fusion? Biologically, yes, fusion is a reality, like yellow and blue seamlessly blending to make green. But culturally, it’s like me ordering sweet and sour pork at a Chinese takeaway at some Aussie town. I can’t stand it. I take it home, rinse off the MSG-laden sauce, pick off all the batter, add lots of yummy broccoli-green gailaan, 木耳 (mu er, literally, wood ear, a wavy black-brown fungus), and lots of other chop-chop vegies. For most of my life, this East-West fusion dish was not AB, but Ab. I would now say that I taste more like a C. So, I'm AbC. 哈哈哈!(Hahaha!)

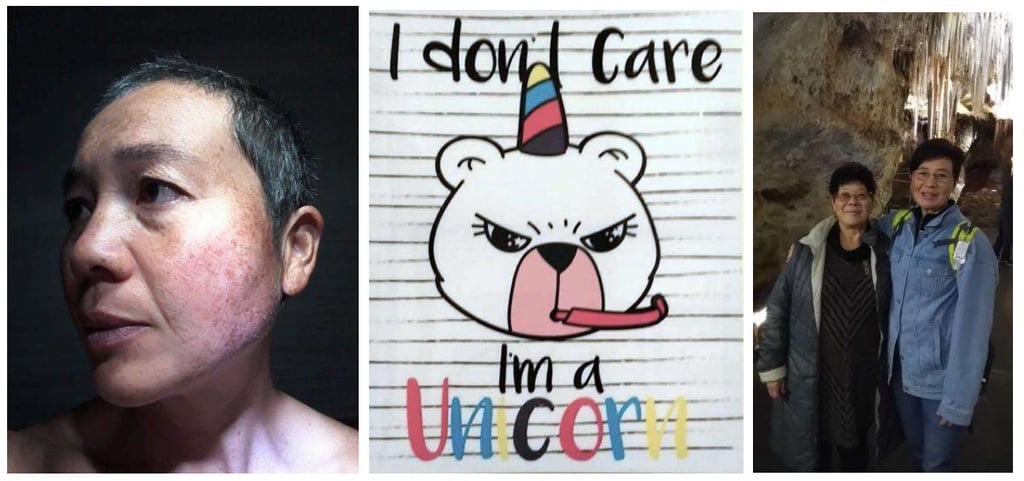

Left: Me, a freckled AbC. Centre: Also me. Right: My mother and I at Tantanoola Caves, SA.